Whiskey & Science

Leading the way to indulgence, descending ten steps, into the bar. Soles squeal on the fresh black surface, the floor has just be repainted. Deep, dark brown leather chairs await. Right at the back a piano, this boss plays here himself too. Now he reaches for the bottle. Stefan Gabányi pours a whiskey. A Longrow Single Malt. The incidence rate is still too high to welcome guests. So these are the only glasses the host will be filling in his bar in Munich this evening.

Indulgence is becoming an endangered way of life. Restaurants, pubs and bars — all long since locked down. For the moment, he’s the homemaker, says Gabányi. The barman is being modest. For 23 years, he worked night after night in the legendary Schumann’s bar in Munich as a recognized whiskey expert. Since 2012, he has been running his own bar, open until five in the morning, when life was normal, with live music once a week. His definitive work “Schumann’s Whisk(e)y Lexicon”, has just been published, translated into English for the international whiskey aficionados. Gabányi pours, just for nosing. But what does that actually mean: Just for nosing? If the nose doesn’t react to this whiskey, it’s high time for a coronavirus test.

“First the peat note,” explains Gabányi. “For some, this is also akin to a medicine, reminiscent of iodine. Then we get the fruit. Cloves too. A touch of salt or pepper...” Dr. Tilman Sauerwald sniffs, concentrating. “There’s a hint of sweetness too,” the expert from the Fraunhofer Institute for Process Engineering and Packaging IVV wracks his brains: “Pear?”

While ever we are breathing, we can smell. 350 receptor types work around the clock, day and night. No matter whether asleep or awake, scent molecules excite the olfactory cells, produce a current that’s directed through the nerve fibers into the brain, reach the brain areas of the limbic system, responsible for emotion and mood, and the hippocampus, responsible for memory and recall. This dedicated circuit makes smelling so immediate — and so difficult for us humans. To express the unfathomable, experts resort to word crutches. Gabányi recounts whiskey tastings in Scotland, where the connoisseurs passionately try to find the best superlatives to describe the bouquet. “Like a wet horse blanket,” he’s even heard. Or even: “This one smells like a seagull’s armpit.”

Dr. Tilman Sauerwald takes a different approach. The physicist and expert for gas measurement technology is the Project Manager in the “Campus of the senses”. Under this initiative, sponsored by the Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Regional Development and Energy, experts from Fraunhofer IVV and the Fraunhofer Institute for Integrated Circuits IIS, working in cooperation with the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, are researching the sense of smell and taste — and are planning to translate these chemosensory perceptions into machine and digital concepts. Together with his team, Sauerwald chose whiskey as the research subject. As a scientist, he is fascinated by the diversity, the wealth of variants, the complexity.

“You have your work cut out there!”, says Gabányi in amazement. “A very complex task indeed,” agrees Sauerwald.

In his bar, the whiskey man explains the diversity of aromas. “The water, that’s very important!”, says Gabányi. As an example, he describes Islay, the Hebrides island battered by storms and famous for the most Scottish of all Scottish whiskeys. The island is covered in peat, which turns the water pale yellow — and alters its taste. This increases the whiskey’s phenol content. Ten ppm in the malt creates a slightly smoky taste, 40 ppm and upwards make it a concoction for specialists. Gabányi also talks about the Scottish pot stills, which would be too impure for German distillers. Precisely why they are able to impart more complex aromas. Then he turns to the casks, for many experts quite simply “the mother of the whiskey”, because this is where 60 to 80 percent of the aroma develops. He talks about the varieties that are left to mature for their last years in specially imported port or sherry casks before being decanted. He describes the differences between European barrel oak, which contains more tannins, and the American oak with its vanilla aroma. He goes on to explain why connoisseurs are so fascinated by individual barrel filling events, because they are so unique, so exclusive and offer an unrepeatable pleasure. After all, every barrel is a limited edition that yields just 300 bottles — sometimes fewer.

At the end of February, a 0.75 liter bottle of “The Macallan 1926 Fine and Rare” was auctioned in Scotland, it fetched 1,157,000 euros. In 1986, just 40 bottles were decanted from the barrel, only 14 of these were labeled Fine and Rare. The world record for a bottle of whiskey is still around half more, at a palatable 1.5 million pounds.

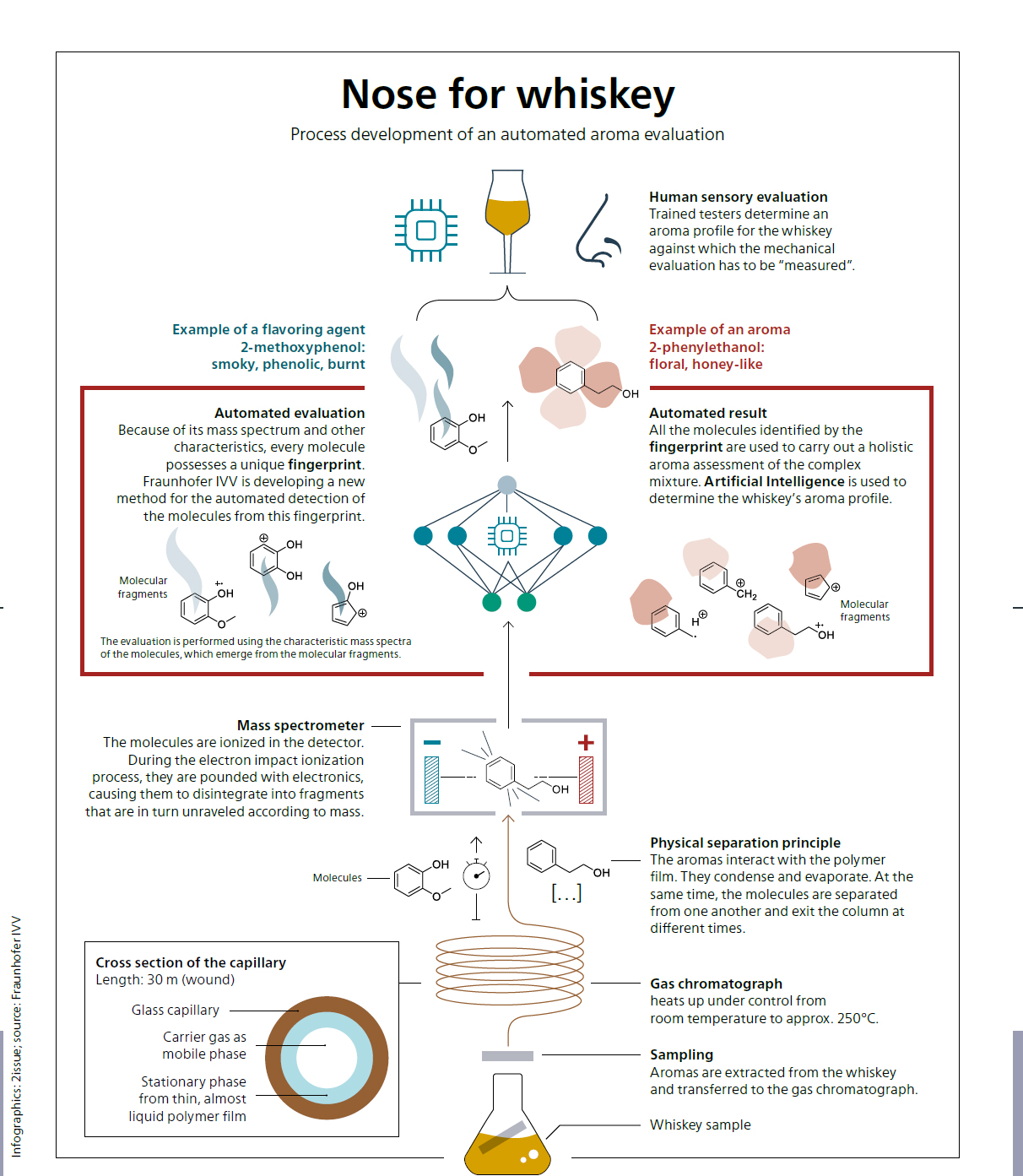

Keeping the sober perspective, the art consists of around 40 flavoring agents. It sounds straightforward. 2-phenylethanol has a floral, honey-like aroma. 2-methoxyphenol smells slightly smoky, burnt. Gamma-Nonalactone is reminiscent of coco, 4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol of cloves. Quercus lactones are produced by the constituents of the oak wood. The interactions between these substances cause the complexity. Furthermore, even closely related chemicals perplex again and again with their dissimilarities. The nose perceives one substance as: Wood. Another as: Rubber.

Dr. Sauerwald brought one of his tools to the bar this evening. A column. A glass capillary, wafer thin and 30 meters in length, is wound to form a loop of 30 centimeters in diameter. Inside is plastic that is almost liquid. This column is placed in an oven at a temperature of 250 to 300 degrees. Gas is introduced, the readily soluble separates from the barely soluble and can be smelled and measured in parallel at different times via a Y-shaped end piece. Deciphering the concert of flavoring agents requires a concert of experts. Sauerwald’s team of engineers and psychologists, food chemists and neuroscientists are working to crack the whiskey aroma code. “We need this interdisciplinarity, especially when it comes to the senses,” explains the Project Manager. “It is indeed a massive challenge, even to get everyone speaking the same language, but it will without any doubt become increasingly important in science — and certainly at Fraunhofer due to the diversity of the institutes.”

The measurement data from the gas chromatograph add up to aroma profiles. Automating this task, still largely a manual one, is one of Tilman Sauerwald’s goals. So far, the scientists have analyzed scotch blends. The data basis of the elected Scottish whiskeys is currently being expanded by selected Germany whiskey varieties. The plan, using this basis, is to have a classification trained by a human sensory panel, that is to say by human testers, by the end of the year. This will show whether the machine is able to class new blends just like a human. Sauerwald puts it in a nutshell: “We are trying to make the senses of smell and taste measurable by machine and in doing so support the creative process of blending.” The ultimate goal is to give the blend masters who mix the major whiskey brands for the reliability of their taste an instrument to support aroma predictions — and a tool for detecting and avoiding off-aromas in good time. 90 percent of scotch is sold over the counter as blended whiskey. Reliability is important here: A Johnny Walker always has to taste like Johnny Walker and a Chivas Regal like Chivas Regal. “My vision,” says Dr. Tilman Sauerwald, “is to one day measure smell and taste as accurately as the other senses like sounds and colors.” A nightmare for Stefan Gabányi, the whiskey man? “This would be a great help to the manufacturers,” he replies. “It’s really very exciting for the industry.” And he adds: “The exclusivity, the creativity, will always remain.”

- Campus of the Senses (campus-der-sinne.fraunhofer.de)