With more than 120 patents, a collection of personal awards and many prizes for her spin-off company specializing in 3D laser lithography, Dr. Ruth Houbertz likes to be on the move, whether in her role as a scientist, company founder, activist or motorcyclist. A successful tech founder and mother, she is a role model and a strong personality with iron-clad principles. She left a position at Sandia National Laboratories in the United States to move to Fraunhofer ISC in Würzburg, where she worked for 14 years. During her time there, she initiated several restructuring measures to strengthen her team’s profile, and ulti-mately merged the optics and electronics divisions. This was a success: She developed a process that uses an optical waveguide to con-nect a vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser (VCSEL) directly to a photodiode, which won her the Joseph von Fraunhofer Prize in 2007. Her team used two-photon absorp-tion (TPA) to shape a material developed at Fraunhofer ISC into three-dimensional structures. Houbertz has continued to develop this process, and in 2013 she trans-ferred it to the spin-off Multiphoton Optics GmbH. As an entrepreneur, she has big plans for the startup, for which she has received numerous accolades and prizes. She sold it in early 2021. Today, Houbertz works with ThinkMade Engineering & Consulting as an advisor to businesses for innovation and technology issues and with SprinD as an innovation manager, as well as being an active member of many committees and trade associa-tions. Her project “Society6.0” is helping to set new standards in education and in-formation for all, part of this native Rhinelander’s commitment to creating a sustaina-ble, responsible society in which nobody is left behind.

Dr. Houbertz, you gave up a secure job at Fraunhofer to pursue the adventure of founding a startup.

I took a chance with the spin-off because I was, and still am, convinced that optical data transfer can solve at least part of the energy problems in data centers. Optical components are capable of transferring each bit of data using a fraction of the energy of an electronic transfer. But there are also many other areas where optical processes can be put to use. For example, smartphones have tiny optical components built into them which can be made even smaller using 3D lithography. The process can also be used to produce ultra-thin optical components with additional functions — a kind of meta-optics. I personally really like this idea, but it’s just one of many examples of ambitious concepts that have plenty of leverage to revolutionize the way we build optics today.

So there are more consumer product implementations still to come?

You can’t look at these things in isolation. These are systems that have to work to-gether, and optical components are no use on their own because there are always interfaces where optical signals need to be converted into electrical information. On top of that, it’s only been two decades since we started integrating optical data trans-fer into a microelectronic world, compared to over 70 years of development in the field of microelectronics. The market forecasts predicted that 2018 would be the year when optical technologies would “take off” — that’s what we’re seeing now, only a couple of years behind schedule.

Could you briefly explain the process you’ve developed?

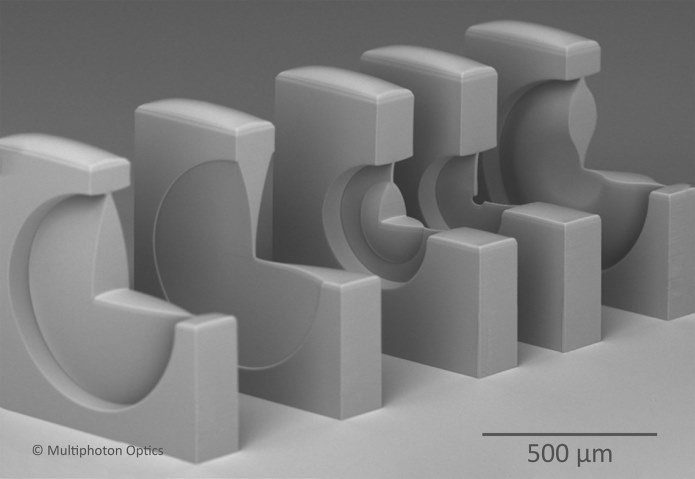

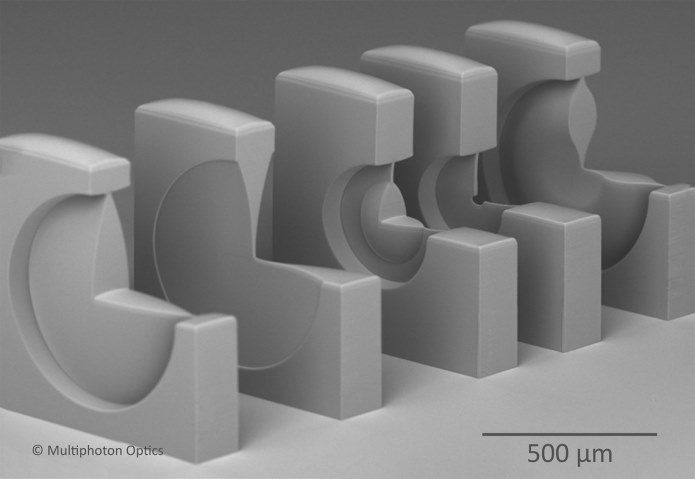

If you pour pancake batter into a pan with some hot and some cold areas, you’ll see a pattern: the batter in the hot areas will cook and harden, and the rest will remain liquid and get poured away. Conventional lithography works in a similar way, using an exposure process with a particular wavelength (or color) of light and a mask contain-ing the structures we want to produce. That’s how we make microelectronic compo-nents like microchips, for example. We can use a liquid that solidifies when exposed to light, and apply a solvent to remove the unexposed material — this process is de-scribed as “additive.” Conversely, we can also use light exposure to break down solid bonds so we can remove certain pieces — this process is “subtractive.” What’s special about the process I’ve developed is that it doesn’t even need a mask; it uses a material that I refined as part of my work on this technology at the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. The light can be directed through this material like ink through a pen, meaning that it has complete freedom of movement. This is what clearly sets us apart from the com-petition. However, the process can also build a three-dimensional structure layer by layer, like with a 3D printer, which is the most common form of structuring. This pro-duces a precision-made 3D structure. What’s unique about Multiphoton Optics is the ability to orchestrate additive and subtractive processes so that complex structures can be constructed and deconstructed in a single machine. That’s why I’ve dedicated around 20 years of my life to the study of light-matter interactions and worked inten-sively with software and control systems.

You’ve collected not only personal awards, but also a number of prestigious prizes for the company you founded, and yet in the spring you agreed to sell it.

Prizes aren’t everything. I actually wanted to turn this company into a unicorn [a startup with a valuation of over a billion dollars], but since then I’ve come to the con-clusion that, apart from Fraunhofer, the investors never understood that chasing a quick buck is not the way to achieve great things. It’s never good to base decisions on fear. With Heidelberg Instruments Microtechnology my startup is in very capable hands, but I would have liked to see for myself the company’s rapid development into worthwhile fields of application. My dream, which I haven’t given up on yet despite the sale of my company, is to reach a new dimension of optical packaging for co-packaged on-board optics and wafer-scale optics with a level of freedom that just isn’t possible with the processes in use today. That would open up completely new possibil-ities: super-thin, extremely light, highly integrable optics. As with everything, though, there’s no black and white, or — in technological terms — good and bad technology. The real art lies in combining technologies and hybrid approaches.

Did personal reasons also factor into the sale?

There’s one thing I can be sure of: If I ever write my memoir, it will start and end with the words, “Stay true to yourself and be passionate and authentic!” If I don’t love what I’m doing, if it’s not fun or if it’s not taking me any further, I leave. That’s how I’ve always done things, even at school. Whenever I’d start to get bored with class, I used to climb out of the window and walk to the market in Aachen to watch and meet other people. To me, that was a much more useful way to spend my time. Whether I’m founding a company or baking with my kids, I only ever do things I believe in and enjoy. We should never compromise ourselves.

So you’re never willing to compromise?

In general, I’m prepared to reach compromises. A harmonious environment is important to me, and that means sometimes you need to go with the flow. The key thing, though, is to ask yourself what you ultimately want to achieve for everyone. I’m a fan of win-win situations, and I will be for the rest of my life. Of course, there’s always the risk of compromising yourself, but that can be avoided through careful reflection. I think Steve Jobs was an admirable example of someone who wouldn’t budge from his principles. If I don’t feel like I’m in the right place, I change the parameters of the job or leave completely. There’s no point making myself unhappy by being around people with no backbone or scientific honesty. Sometimes it takes a little longer for me because I put feeling and emotion into everything I do. Ultimately, though, I’m taking this chance because every change in life takes us to a new level, usually a much better one than the last. We have the choice to keep an open mind and turn negatives into positives.

There were times in my professional life when I felt like I was losing my identity — as I always say in mentoring programs or podium discussions, if you notice that happening, leave! Change something! Even though it can be hard sometimes. After all, I didn’t know if my independent career or the Society6.0 project would work. After the sale, I actually got a very lucrative job offer from the US. I want my own life and not to have to do what other people expect of me, though, so I decided to turn it down. For me, creativity only happens when I can think freely. Because of that, I chose uncertainty again, even though it was a tempting prospect to work in a cutting-edge major corporation.